Nourishing life is not just about physical or breathing exercises, it is cultivating the art of living in all its rich variety and interest. Underneath all of that rich variety, however, is a unity of being that is ultimately supportive and nourishing; most traditional societies know this, and are structured to foster this understanding over the course of a life.

I remember one day back in China when I was young, I heard three teachers of completely different disciplines use the same words to describe what they were doing. At a morning Taichi class, the teacher said ‘Your qi must reach the tip of the sword, just as if it were reaching the tip of your finger!’ At noon, the calligraphy teacher insisted ‘Don’t just hold the brush in your hand – the qi must flow through and reach through the brush into the ink!’ And later I heard an acupuncture teacher explaining to a beginner: ‘Stand properly! Your intent must pass into the needle, and your qi must flow to the tip of the needle. Only then can you rectify the qi of the patient!’

That was when I realized that the whole of Chinese traditional society was designed to foster an understanding of fundamental cosmic principles, learned by experience, and by different experiences in different disciplines. The goal of this was to produce a complete person, a real human being.

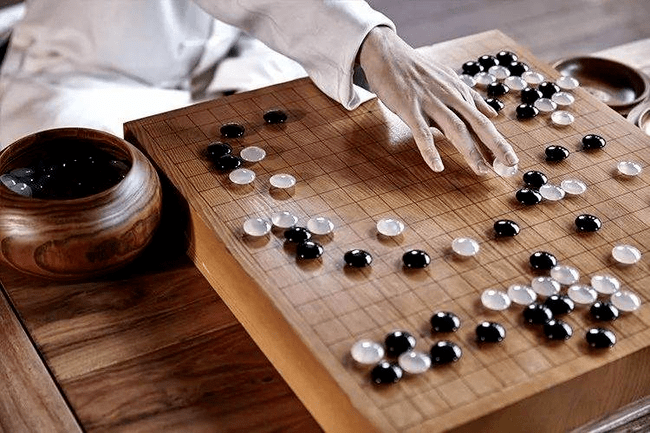

A gentleman (and many women) in traditional China would learn music, calligraphy, painting and the game of Weiqi (‘surrounding chess’). Qín qí shū huà were the four arts of the cultivated person, literally ‘zither, chess, writing and painting’. All of these arts introduce different facets of the same cosmic principles. Let us take the most apparently trivial: Weiqi.

According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Weiqi, or as it is mainly known in the West, Go (from its Japanese name I-go), was invented in China in 2306 BC. Confucius mentioned it in his Analects in the 6th century BC. There is a first century AD text dedicated to Go still extant. At present there are approximately 10 million Go players in the world at the ‘strong beginner’ level or better. Melbourne hosts an annual Australian Go championship.

How to play

The game is very simple: There are 361 identical black and white round pieces, called ‘stones’. These are used to mark off territory. The winner has the most territory.

You begin with an empty board marked with nineteen lines horizontally and nineteen lines vertically. Black begins by placing a stone at any of the intersections of those lines, then white follows, placing a stone at any other intersection. Stones do not move, and the pieces remain on the board unless captured. A piece is captured when it, or a group it is linked with, has no connection with open intersections – no ‘breathing space.’ The game is over when both players agree to end.

Despite this simplicity, only in the last few years were computer programs developed that could beat a strong beginner in Go. That had been a premier challenge in AI for the last twenty years.

Famous Players

Confucius and Mencius both mention the game. All the principles in Sun Zi’s Art of War apply perfectly to Go (much more so than to chess). Legend has it that the Daoist patriarch Lu Dong-Bin (‘Guest of the Cavern’) was an exceedingly skilful hand at Weiqi. It is a matter of history that the Japanese Tokugawa government subsidized Go education as a matter of national importance for 250 years. The German mathematician Liebniz described a game of Go in Europe in the 16th century – he was also intrigued by the Yi Jing (Book of Changes). Mao Tse-Tong was a consummate player,[1] and it is argued that this contributed in no small way to his success at guerrilla warfare.

The principles of the universe

What are the ‘cosmic principles’ one would learn by playing Weiqi? Normally, one would simply play the game, and subtly absorb the principles in the usual Daoist way; ‘learning without words.’ Of course, if a student was particularly slow, one’s Weiqi master would point these things out. Here is what my Weiqi master told me:

The board is square ‘like the earth’[2], the lens-shaped stones are round ‘like the sky’. There are nineteen lines on each side, which gives 361 intersections, ‘like the days of the year’. The four sides are like the four seasons, and the four directions.

Movement takes place against an unmoving background, the sky moving over the unmoving earth, the stones placed on an unmoving board. The stones are black and white, yin and yang; and also like yin and yang, players alternate moves (in ancient times, for this reason, players were not allowed to ‘pass’).

As the Yi Jing – Classic of Changes – describes infinite change, no game is ever the same: the board is empty at the start, and the interplay of forces creates a unique pattern, a pattern that remains visible at the end of the game.

Without qi, a stone or group of stones is dead – it must have ‘breathing space.’ As lines of stones take shape into groups, they map the ebb and flow of qi across the board; those groups with much qi are lively and free, those which are constricted and ‘heavy’ often die.

During the course of play, a player’s fortunes change frequently, as in life; how the player reacts to these changes can tell them (and everyone else watching) what degree of cultivation they have reached.

Do they lose with grace? Do they win kindly?

Do they play impulsively, or calculate each move?

One can become obsessed with a small portion of the board, completely missing the momentous changes happening elsewhere. Or one can learn to view the total situation, objectively, even wisely – but this wisdom is usually learned over a long painful apprenticeship, with many lost games.

‘One improves in the game by learning to see,’ I was told.

‘See what?’ I asked.

‘What is in front of your face all the time!’ my teacher laughed. ‘You will learn to see the patterns that will determine what is to come, and when you learn to see those patterns on this board, you may learn how to see those patterns in life, as well.’

Endnotes:

[1] There is even a book entitled: The Protracted Game: A Wei-Ch’i Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy.

[2] China was thought to be like a go-board, square and divided into a 9×9 grid, and floating on and surrounded by water. Even today, weiqi beginners learn on a board of 9×9 lines.