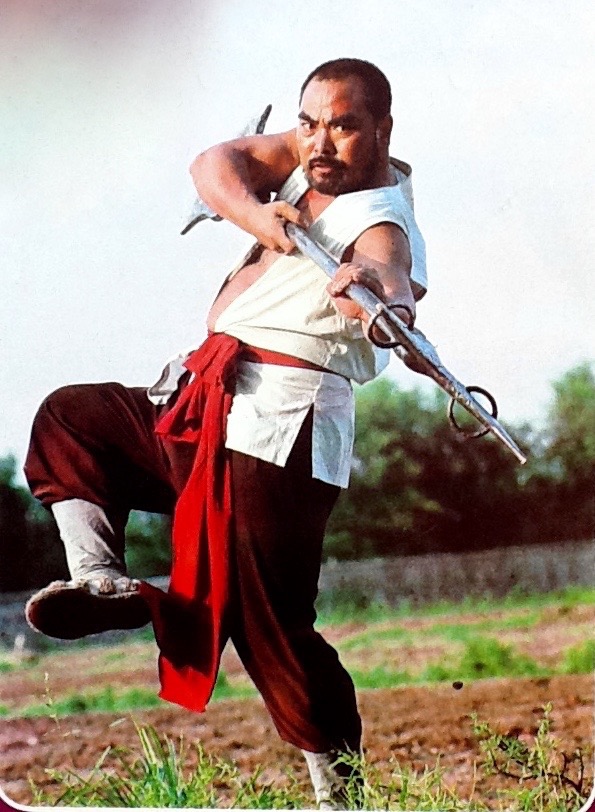

The heavy wooden staff whistled as it swung sharply down toward my head. Just in time I caught it with the tip of my own staff. I deflected it clockwise and then continued the circle, quickly scraping my staff down along the inside of his. With his wrist attacked, he would have to either drop his grip from the staff or get hit. Unexpectedly, the fat Taoist – surprisingly agile as many hefty people are – pivoted his staff vertically. This shifted his hands out of the way so that my staff just slid off into nothing. In the same movement he circled his rear leg behind mine, followed closely by his hip and shoulder in a solid ‘bump!’ that threw me backwards over his leg and into the dust.

It was not the first time.

He chuckled as he helped me up. “You were focused too much on my staff,” he said. “When I changed to use my body as the weapon, you missed the shift. Remember Dào Dé Jīng chapter 16? Take emptiness to the extreme, maintain stillness firmly. The ten thousand things move together, as I watch the return. Flexibility, and not getting too attached to a particular point of view, this is crucial if you are going to remain a viable entity.”

We had been training together and sparring on and off for the last few days on the cleared flat space in the hills above his monastery. This overlooked the mist-covered lake and the mountains on the far side, now purple in the early dawn. In between training sessions we talked about a range of topics, and I was surprised to find he was remarkably well-informed about life outside the monastery.

“My teacher at Wu Dang impressed upon me that ‘being a monk’ is a temporary state, a stage you adopt to refine aspects of yourself that require a period of quiet living. It should not be permanent, and definitely should not be adopted to run away and hide from life, cutting yourself off from the world. You must take the benefits of your training out into the world to help others in any way you can. It is sort of like meditation – its easy enough to attain stillness in a quiet room, but it is only really useful when you can maintain that stillness in the hurly-burly of life.”

“Not all of the monks follow that of course. In fact, few do. That was one of the things the Abbott wanted to talk to me about the other day. He said my ideas were a bit too radical, and were disturbing the other monks. I said this was the training of my teacher at Wu Dang, which I had found by experience to be valuable, although I did admit that some aspects were unorthodox.”

‘Why was that teacher at Wu Dang like that?’ I said.

‘I think it was because he became a Daoist monk later in life, and had been exposed to other ideas along the way. I know he spent a lot of his earlier life in the northwest, around Linxia, but otherwise I just remember him as very special. The Abbott however said that I should try to fit in a bit better and not rock the boat, or I’d be in trouble.”

I said something about the institution stifling the very thing it was there to develop, and he replied “Actually the Abbott knew exactly what I was talking about. He also had a teacher like that, and he had also got into trouble earlier on.”

He stopped to pull up his leggings before going on: “But now he works within the system, keeping an eye out for young monks with potential, and steering them towards places and teachers that could help them the most. The others, who just wanted a soft life, he leaves alone.”

A teacher like that will often try to put you off, rather than try to attract you. Your reaction to this type of deflection will say a lot about you, your perception and your capacity.

The fat monk stood up, leaned on his staff, and said: “You know, I have found we are often watched, first to see if we show interest, and then later, capacity; whether we know it or not. We are often helped, even if we do not register it. People who look quite ordinary may be much more advanced than you think, and may even be teaching others, quietly, without anyone else being aware of it. You cannot really tell from the outside. Such a teacher would not be obvious by their piety or the way they dress or any other external indication.”

Letting go, giving way

This was a new idea for me. “So why would they do that? And then how can you tell who a realized teacher is?”

He thought for a second. “Well, one reason is that anyone can dress like a Buddhist monk or a Daoist priest – you just put on the garments; what does that change? It’s the inside that counts. Furthermore a teacher like that, a really realized teacher, will often try to put you off, rather than try to attract you. Your reaction to this type of deflection will say a lot about you, your perception and your capacity. In any case, there are plenty of things that you must teach yourself before you ever need a high-level teacher. Many things in fact convey sustenance for your inner being, although on the outside they look completely ordinary. Some literature is like that.”

I had not really taken all these ideas in, but didn’t want to show it. I had caught my breath, and was ready for some more workout. I challenged him to push hands, a soft form of taichi sparring, in which as little brute strength as possible is used, while still aiming to control the other person.

‘Hmm, not bad!’ he said after a few minutes of simple circular pushing. “you are quite soft, and yet still have that tensile resiliency that gives the quality of peng energy to your contact with the opponent. What would you do if I grabbed you like this?”

He grabbed my hand with a grip like a bear. Rather than try to pull back and jerk free, I went with and followed his pull, and folded my elbow over his arm, forcing his hand into an untenable position from which he had no choice but to let go.

“Good!” he said, breaking off and standing apart. “But how did you do that?”

He did not wait for an answer, but provided it himself, gesturing to my hand, while his bright eyes flashed.

“You let go of your idea ‘He has my hand!’ and you gave up your hand to me. Then you very generously also added an elbow.” He laughed.

“That was too much for me, so I had to release you. Letting go, giving way, giving away – these are deep principles that apply to a well-lived life as much as they do to skillful taichi practice.”

He paused for a moment, apparently caught by an idea, and held up his hand as I started to say something, then continued: “Sorry, but I feel its important to tell you this. I can truly say that whatever I have given away has always been repaid many times over. Whether it is money, or assistance, or affection, as long as it is given without looking for some reward, one is always rewarded. The frightening thing is that that applies not only to good things, if people only knew it.”

A striking point

I was touched, and slightly embarrassed by that fact. That was when I realized that in the West we are not used anymore to straight talk about generosity or affection, everything has to be cynical or hard-nosed. The realization saddened me, because then I knew it diminished us as human beings. To change the subject I asked him about striking acupuncture points to cause paralysis, which was a staple of Chinese gongfu novels and movies. To my surprise, he agreed that it was possible.

“Paralysis, though, means incapacity for further attack” he explained. “You don’t have to completely freeze someone like in the movies, you just have to make it practically impossible for them to use a limb. That’s enough.”

“But just by striking a single acupuncture point?” I asked, still incredulous.

“Certainly!” he said.

My doubts continued, and finally I expressed them, and basically insisted on a demonstration, even though he warned that I would not like it.

He directed me to adopt a typical defensive posture, which I did, right hand and foot forward, which he matched. Suddenly he sprang forward and flicked his front hand over palm up, just brushing my eyelids. I blinked reflexively. At almost the same time I felt a solid whack! to the back of my right lower leg, and instantly the muscles of my right calf balled into a solid knot. It was like a stretched spring suddenly cut loose from one end. The pain was excruciating, and did not stop. I hopped around on one leg briefly, then fell over in the dirt grabbing my leg, trying desperately to massage some life back into the muscle.

“I said you would not like it,” he said, with an innocent look. “That was the single point Cheng Shan.¹ When you blinked, I had a chance to sweep my right foot in, then hook it so it would catch you just below the belly of the gastrocnemius muscle, where the point is. Struck at that angle, with enough force, it causes intense cramp. You will be completely out of action for a few minutes, but you will be walking normally within a day or two. Or three,” he added thoughtfully. “When my teacher did that to me it was three days before I was not limping.”

I groaned, but was not angry or resentful. I was actually happy to have experienced the reality of what was often dismissed as legend, and said as much.

He agreed. “Yes, I felt something like that too. Learning can be painful, but there is nothing like experience. I’ll get our stuff together, and when you can walk, we’ll head down for some breakfast: rice porridge. And I heard Cook is making some jianbing today: spring onion buns.”

Chen Village breathing

But I could not walk just yet. While we waited he showed me the special breathing method from Chen Jia Gou, the village home of Chen style taichi, a method they used in between practice sets:

One sits with hands resting on the knees, back straight but not stiff, with the chin drawn in just enough to feel the back stretch. The mind is kept on the breath until it settles and sinks into the Dan Tian, and you hold that for a while, then when it feels appropriate you gently guide the qi from the Dan Tian up to the shoulder of the right arm, then down to the fingers of the right hand, then back up to the shoulder, then down to the right knee, and then back up the leg and into the Dan Tian once again. From here the qi goes to the left knee, then back and up to the left shoulder and down to the tips of the left hand, then back to the Dan Tian.

“The order isn’t important,” he said, as he demonstrated the posture. “This is right arm, right leg, left leg, left arm, but it can be varied. For example, you can do right leg then left arm or vice-versa, or even better just let the qi flow naturally as it prefers. Once it is flowing naturally, the next taichi set you do will be very spirited and lively: gu dang jing shen le, you have drummed up the qi.”

“But it is not using your mind to try to force the qi to circle when it is not ready; that would be counter-productive. It is more like allowing it to flow there. It is best to just let it be natural, as it will certainly move by itself when ready. Anyway, you can exhaust the qi by trying to force it, and you definitely do not want to do that. You need to accumulate energy, not dissipate it.”

“Are you familiar with the Chuán Dào Jí?” he asked. “I was just reading it again last night, and there is a passage that says,” and he paused, shut his eyes and recited:

What you breathe out is your own yuan qi, which emerges from the center. What you breathe in is the zheng qi of heaven and earth, entering from the outside. If your root source is firm and fixed and your yuan qi is not damaged, then during your breathing you can obtain the zheng qi of heaven and earth. But if your root source is not firm, your essence exhausted, and the qi weak, then from the upper body your own yuan qi leaks out, while in the lower body the chamber of the fundamental (ben gong) is not strengthened. The zheng qi of heaven and earth that you breath in just goes out again when you exhale. The yuan qi within your body will no longer be yours, but rather be stolen away by heaven and earth.²

“This tells us something crucial,” he said. “If you have been careless throughout your life, and weakened your Kidney jing, then before you can make much progress in studying Daoism you will have to repair the damage. If your jing/vitality is still strong, then you can begin to accumulate the energy needed to progress. But this passage leaves out a crucial part of the technique. Say, how is your leg feeling? Can you walk yet?” He squatted down and gave my calf a vigorous rub.

“Its fine.” I said, even though it wasn’t, really. I stood up, and managed to hobble toward the path leading down to the monastery, where breakfast awaited. I let the silence grow between us for a while as we walked, and finally burst out “Ok, I’ll bite. What is the crucial part of the technique?!”

The fat Daoist laughed delightedly as he ambled down the path, considerately reducing the pace for me. He said “I just wanted to see if you were listening. But there is a crucial part to absorbing the zheng qi of heaven and earth through breathing, and that is your attention. You must attend to your breath to accumulate that energy with any semblance of efficiency, consciously absorbing the qi from the air and storing it low in the Dan Tian. Of course this works better where the qi is good, like around here, or in deep quiet forests, or at waterfalls. Early morning is best, as you know.”

“When you inhale deeply, then … whoah – can you smell that? Cook has outdone himself today. Look, I’ll just go on ahead and save you a place, ok?” Before I could even respond he had bounded off down the path, rounded a corner and was out of sight. I shuffled along after as quickly as I could, muttering imprecations, imagining the monastery kitchen thoroughly picked clean by the less-than-abstemious monks.

In the kitchen

“There is no sin in good food” the fat monk grinned, his mouth full of green, when I challenged him about this. I had collected my own congee and spring onion buns, and sat down where he had saved me a place, true to his word. “Its all about balance, as you know very well. Food that is made with high quality attention and eaten with enjoyment is extremely nourishing on many levels. Just don’t be greedy, and stop eating while you are still a little bit hungry – as the nourishment begins to enter the system the rest of your hunger will disappear. That also leaves room for Spleen qi to work. Overloading the Stomach oppresses the Spleen, and in fact diminishes the nutrition one can obtain. You eat more, but get less, so to speak. That is particularly true for richer foods and meats.”

As we left the kitchen I saw a few glances at my limp from some of the other monks, and a few stifled grins quickly buried in bowls of congee. The fat monk noticed, and before I could say anything smiled cheekily and said “They wanted to know where you were, so I had to tell them. Don’t worry, a couple of them have had limps like yours before too. There is no malice in their look, they know exactly how you feel. Come on, let’s head down to the library. I’m a bit late opening up again. The abbot will be cross.”

I asked him about something he had mentioned the first day I met him, about how you could not read the Dào Dé Jīng like a novel, but rather had to savour it like fine wine.

We reached the library, where we had first met the week before. He took down the wooden beam and pushed open the double doors, letting sunshine in to illuminate the dust now swirling in eddies over the stone floor. He gestured to the wooden seat I had found most comfortable in recent days, and set about making some tea. As he collected his tea implements, I asked him about something he had mentioned the first day I met him, about how you could not read the Dào Dé Jīng like a novel, but rather had to savour it like fine wine.

Savouring the Dào Dé Jīng

“I think my example was hard candy!” he laughed, and then bent over to light the tea stove. When he straightened up, he was silent for a moment, looking up at the stacks of books. Then he said “I think I can give you an example of how texts in this area are multi-layered, and just how carefully they need to be read. We were talking last time about dé, and how it is a type of energy you must accumulate before you can make the choices which allow you to accord with the Dào. Well, the Dào Dé Jīng talks a lot about dé and its relation to Dào, but when it does, the words have to be read slowly and considered from a number of different angles. Here,” he said, taking down a large copy of Lao Zi from the shelf and opening it. “Chapter 21 says: 孔德之容惟道是从。kŏng dé zhī róng, weī dào shì cóng.”

He stopped and looked at me, and I hurriedly said:

“Yes, I have read that chapter.”

“Ah, but how carefully?” he asked. “These eight words are like a manual of dé, directions in how to begin to gather it, and its function. I have Wang Bi’s commentary here, and he defined the first word like this:

孔德之容惟道是从。

Kŏng is kōng. 孔空也。Kong means empty. It is only because of empty space that dé is so. Afterwards, it is then able to move from Dào.

“So the first prerequisite for dé is emptiness. You have let go of everything that blocks it from entering. But then, according to He Shang-Gong, kŏng also means ‘great,’ which defines the quality of the dé. That is just the first word. The second word is dé, the third is a grammatical particle, and the fourth word is róng.”

The fat monk paused for a second, reached over and took a sip of tea, then continued:

“Róng means to contain, and so these first four words could mean simply ‘emptiness is the container of this great dé.’ However the commentator Gao Xiang says that róng (容) also means to move or act. Thus the same four words also mean ‘emptiness is the movement of the dé’ or ‘the action of the dé is in emptiness’ or ‘the movement of the great dé’.”

Someone entered the library, called a loud greeting, and the fat monk leapt up to serve them. This gave me a chance to make some notes. When he returned, he asked “Sorry about that. Now, where were we?”

I recited: “The first four words of the 21st chapter mean all of the following:

a) emptiness is the container of this great dé

b) emptiness is the movement of the dé

c) the action of the dé is in emptiness, or simply

d) the movement of the great dé.”

He went on: “Right. Then, when you add the last four words ‘only in accordance with the Dào’ – wei Dào shi cóng— you get ‘the action of this great dé is to move with the Dào and only with the Dào.’ And of course the other meanings of all the words must be kept in your head at the same time to really appreciate its textured wholeness.”

“All of these aspects of those eight words apply simultaneously,” the fat Daoist said, “and so you can see how rich this text is, and that is why it cannot be read like a novel, you have to savour it, read it under different conditions, in different mind sets, even at different ages in your life. It will give up its meanings as you are able to see them.”

He poured us both another cup of tea.

“The key thing to know and remember, ‘he said ‘is what we said before: that dé is a type of energy that you need in order to begin to make the choices that will allow you to approach the Dào. You access this type of energy by learning to empty yourself of habitual fixations, and also by eventually learning to act in accordance with the Dào. The more you empty yourself through stillness and move from the Dào, the more this dé can move through you. It supports you internally, and manifests as a quality of presence, charisma, power.”

Hidden power

He paused briefly, and then said reflectively “Although those who have this dé often go out of their way to hide the fact.”

“Why is that?” I asked, intrigued as to why someone would try to hide their charisma.

“I asked my teacher the same thing, and he told me a story of a man who had some rare thirty-year-old wine. A friend of a friend visited him, asked for a taste, and was offended when it was refused. The man with the wine said ‘Well, it wouldn’t have lasted thirty years if I kept giving it away, would it?’ The dé is there for a function, not to entertain casual sensation-seekers. It is subtle, and easily drains away. It takes a cultivated attention and a certain mental posture to maintain it.”

He left me alone to go and serve someone else who came in, and when he returned I said “ So what is that mental posture needed to maintain the dé? You’ve already mentioned stillness, and emptiness as a key. Is that all?”

“Those are crucial,” he answered, “but not all. Again it is a balance between actively emptying yourself and remaining still. You can’t try too hard, but neither can you do nothing. Wei wu wei. Do not-doing. You should reach the stage where you do not actually use any effort at all. Let those fixations go, by not holding on to them. Breaking up habits helps us to break up our fixed ideas of the world, and just by the way also stops us becoming boring and predictable. Breaking up fixations also makes space for different aspects of life to enter. And one last aspect of that mental posture, one that helps with emptying ourself, is putting yourself last, putting yourself below. Don’t you remember all the talk of valleys in Lao Zi?”

He who speaks does not know

But my mind had wandered. And anyway by then I was pretty thoroughly tired of being lectured to. Some part of me had the urge to try and score a point, and I said: “You are telling me all these things, but I thought Lao Zi said ‘the sage handles affairs without acting, and teaches without using words’. And didn’t he also say ‘he who knows does not speak, he who speaks does not know’?!”

The fat Daoist looked surprised for a second, then threw back his head and laughed. “For one thing,” he said, “I am no sage. And I am most definitely not your teacher – that is quite a special relationship, not entered into lightly. In any case, the best teacher can teach without words, but it takes the best student to learn that way. I’m not sure you fit the bill. We are simply discussing things of mutual interest – or at least, I thought we were.” He cocked his eyebrow at me.

I was feeling a bit sheepish by then, and covered it by taking a sip of tea.

He continued “Its true that Lao Zi did say ‘he who knows does not speak, he who speaks does not know’ but then he went ahead and wrote a book about it – so what does that fact tell us? First, just what the first chapter says: you can talk about it, but don’t mistake the words for the real thing. Also don’t get stuck on the words, and you should try to get beyond the words as soon as you can. The problem is, very few people can learn without some sort of verbal guidance, and that is more true now than in the past. We tend to be lazy, and generally do not pay attention, and expect everything handed to us. If we woke up and looked around, the teaching is actually everywhere around us.”

Teaching without words

I looked around, and he laughed again. “You asked about teaching without words. As I said, it is the rare student who can benefit from this. I will give you an example, but remember that it actually had to be pointed out to me before I noticed it. My teacher used to have a magnificent hardbound copy of the Dào Dé Jīng, and I was scandalized one day to find him using it as a doorstop. This beautiful and sacred book, there on the dusty floor, used in this disrespectful way, simply to keep the door open. I protested, and offered to find him a brick, but he laughed, called me an idiot, and told me to use the brick on my own head, because that book was there to keep the door open.”

I began to get a glimmer of what he meant.

“So there,” the fat monk said, “all at one and the same time my teacher was illustrating a wide spectrum of meanings: how one can do wu wei – not-doing; how one can teach without words; showing me my fixations and how they limited me; demonstrating the everyday blindness of most people; showing how the teaching surrounds us if we only open our eyes and look; how a knowledge of the relationships between objects can be manipulated to convey meaning, and also, from the other side, how ignorant people may take something of great value and potential and use it in a stupid way that is completely wasteful. And there is much more to be had from that simple example, but I’ll let you chew on it yourself.”

His words had an unusual effect. I felt strangely aware. The room felt alive, three dimensional, almost humming; a waft of incense floated in from the courtyard outside and mixed with the musky smell of the old wood and tea. The dust motes danced slowly in the sunlight, and they had a significance and a meaning I had not perceived before. The stone floor felt more solid; the wooden door-frame seemed alive, and beckoned to a world beyond. Time congealed. I became aware of a deep place within me that moved with those motes, that was one with that door, and knew that the world beyond was a living land of mystery where one could wander in a landscape of meaning. At that moment, the monastery bell tolled, and the sound was a physical wave that moved through me, and I went deep within.

Centuries later I surfaced, to find that seemingly only a moment had passed. The fat Daoist opened his eyes soon after I did, having apparently slipped into a brown study while I had been silent, and reached forward to pick up the teapot.

“More tea?” he asked.

——————-

Endnotes:

1. The acupuncture point UB-57.

2.《钟吕传道集》Collection of Transmissions of the Way – in the form of a discussion between Zhong-Li Quan and Lü Dong-Bin, two of the greatest Tang dynasty Daoist alchemists.

Click here for the pdf of this article: