written by the Gatekeeper

(excerpt)

修煉之道,不外神氣二者;調之養之,返乎元始之天而已。在先天,氣渾於無象,厚重常安;神寓於無形,虛靈難 狀。

The path of cultivation is none other than spirit and qi; harmonizing them, nourishing them, until the return to the primal Heaven.

While in pre-Heaven, qi is indistinct and formless, profound and weighty, constantly peaceful. Spirit resides in the shapeless, empty, lively and hard to describe.

一到後天,氣之重者而輕揚,神之靜者而躁動。氣不如先天之活潑,常氤氳而化醇;神不似先天之光明,脫根塵而獨耀。此命之所以不立,性之所以難修也。

But once in post-Heaven, the weightiness of qi becomes light and lifts, the quietude of spirit becomes disturbed and moves. The qi lacks the agility of the pre-Heaven; yin and yang mix into a rich complexity. The spirit lacks pre-Heaven’s clear brightness in which the contamination of the senses has been thrown off. This is the reason that Life cannot be set up and Essence cannot be refined.

學者欲得長生,須知氣必歸根。夫根何以歸哉?必以氣之輕浮者,複還於敦厚之域,屹然矗立,凝然一團,則氣還於命,而浩浩其天矣;以神之躁妄者,複歸於澄徹之鄉,了了常明,如如自在,則神還於性,而渾渾無極矣。

If those who study this desire a long life, they need to know that qi must return to its root. But how can it return to that root? It must be through taking the light floating qi and returning it once again to the realm of solid sincerity, standing majestically, congealing into a ball and then qi circles back into Life so that Heaven is vast and endless. Likewise, take the frenetic restlessness of the spirit and return it to the land of limpid clarity, knowing clearly with constant illumination, natural and all-of-itself. Then spirit comes back to Essence and undifferentiated infinity.

人奈何只見其小而不從其大耶?噫嘻痛矣!此言水輕而浮,為後天之氣,屬外藥;金沉而重,為先天之命,號真鉛——又號金丹,又號白虎初弦之氣,其名不一,是為內藥。先天金生水,為順行之常道,生人以之,故曰重為輕根。

Why do people only see the petty but do not comply with the great? This is referring to water that is light and floating being the qi of post-Heaven, which is the external medicine; and metal which is heavy and sinking being the pre-Heaven Life (also signified as True Lead, also signified as the Golden Elixir, or the qi of the first crescent of the White Tiger; the names will vary): this is the internal medicine.

In the pre-Heaven metal generates water, this being the normal course of the eternal Dao; humans are generated using this, and this is why Laozi says “Heaviness is the root of lightness.”

夫人生於後天,純是狂蕩輕浮之氣作事,以故水氣輕而浮,情欲多生,命寶喪失,所以易老而衰。君子有逆修之法,無非水複生金,輕返於重,以複乎天元一氣。是以終日行之,而不離乎輜重。不過亭亭矗矗,屹然特立,厚重不遷,養成浩氣,充塞乾坤而已矣。

Now humans are born in the post-Heaven, which is all crazed chaotic floating qi in operation, emotions and desires proliferate, precious Life is squandered, and thus one easily ages and dies.

The Junzi has a method of refinement by reversing this, which is basically water restoratively giving birth to metal. Lightness goes back into Heaviness, and returns to Heaven’s primal unified qi.

Hence one “travels all day without leaving the supply wagon.” There is only standing tall and upright, towering, majestic, capacious and unchanging, cultivating a noble spirit— which is to say, simply filling Qian and Kun.

此為逆修之仙道,煉丹以之。總之由有形以複無形,丹道之一事也。火燥而動,為後天之神,屬外藥;木靜而凝,為先天之元性,曰真汞,曰真精,又曰青龍、真一之氣,其名亦多,要皆內藥。先天木生火,為順行之常道,生人以之,故曰「靜為躁君」。

This Immortal’s Path of reverse cultivation is used in refining the elixir. But to summit up, “form” is returned to “formlessness”—a matter of the Dao of the elixir.

Fiery restlessness moves and becomes the spirit of post-Heaven: this is external medicine.

Wood quietens and congeals, becoming the primal essence of pre-Heaven (also called True Mercury, also called True Vitality, also called the Green Dragon, or the True Unified Qi; the names are various) and all of them are the internal medicine.

Pre-Heaven wood generates fire, the normal progression order of the Dao, by this means humans are given life, and so it is said: “Quietude is the Lord of Restlessness”.

Nourishing life is not just about physical or breathing exercises, it is cultivating the art of living in all its rich variety and interest. Underneath all of that rich variety, however, is a unity of being that is ultimately supportive and nourishing; most traditional societies know this, and are structured to foster this understanding over the course of a life.

I remember one day back in China when I was young, I heard three teachers of completely different disciplines use the same words to describe what they were doing. At a morning Taichi class, the teacher said ‘Your qi must reach the tip of the sword, just as if it were reaching the tip of your finger!’ At noon, the calligraphy teacher insisted ‘Don’t just hold the brush in your hand – the qi must flow through and reach through the brush into the ink!’ And later I heard an acupuncture teacher explaining to a beginner: ‘Stand properly! Your intent must pass into the needle, and your qi must flow to the tip of the needle. Only then can you rectify the qi of the patient!’

That was when I realized that the whole of Chinese traditional society was designed to foster an understanding of fundamental cosmic principles, learned by experience, and by different experiences in different disciplines. The goal of this was to produce a complete person, a real human being.

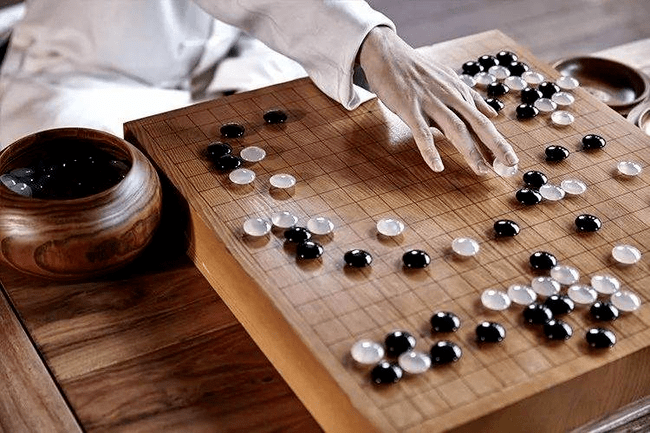

A gentleman (and many women) in traditional China would learn music, calligraphy, painting and the game of Weiqi (‘surrounding chess’). Qín qí shū huà were the four arts of the cultivated person, literally ‘zither, chess, writing and painting’. All of these arts introduce different facets of the same cosmic principles. Let us take the most apparently trivial: Weiqi.

According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Weiqi, or as it is mainly known in the West, Go (from its Japanese name I-go), was invented in China in 2306 BC. Confucius mentioned it in his Analects in the 6th century BC. There is a first century AD text dedicated to Go still extant. At present there are approximately 10 million Go players in the world at the ‘strong beginner’ level or better. Melbourne hosts an annual Australian Go championship.

How to play

The game is very simple: There are 361 identical black and white round pieces, called ‘stones’. These are used to mark off territory. The winner has the most territory.

You begin with an empty board marked with nineteen lines horizontally and nineteen lines vertically. Black begins by placing a stone at any of the intersections of those lines, then white follows, placing a stone at any other intersection. Stones do not move, and the pieces remain on the board unless captured. A piece is captured when it, or a group it is linked with, has no connection with open intersections – no ‘breathing space.’ The game is over when both players agree to end.

Despite this simplicity, only in the last few years were computer programs developed that could beat a strong beginner in Go. That had been a premier challenge in AI for the last twenty years.

Famous Players

Confucius and Mencius both mention the game. All the principles in Sun Zi’s Art of War apply perfectly to Go (much more so than to chess). Legend has it that the Daoist patriarch Lu Dong-Bin (‘Guest of the Cavern’) was an exceedingly skilful hand at Weiqi. It is a matter of history that the Japanese Tokugawa government subsidized Go education as a matter of national importance for 250 years. The German mathematician Liebniz described a game of Go in Europe in the 16th century – he was also intrigued by the Yi Jing (Book of Changes). Mao Tse-Tong was a consummate player,[1] and it is argued that this contributed in no small way to his success at guerrilla warfare.

The principles of the universe

What are the ‘cosmic principles’ one would learn by playing Weiqi? Normally, one would simply play the game, and subtly absorb the principles in the usual Daoist way; ‘learning without words.’ Of course, if a student was particularly slow, one’s Weiqi master would point these things out. Here is what my Weiqi master told me:

The board is square ‘like the earth’[2], the lens-shaped stones are round ‘like the sky’. There are nineteen lines on each side, which gives 361 intersections, ‘like the days of the year’. The four sides are like the four seasons, and the four directions.

Movement takes place against an unmoving background, the sky moving over the unmoving earth, the stones placed on an unmoving board. The stones are black and white, yin and yang; and also like yin and yang, players alternate moves (in ancient times, for this reason, players were not allowed to ‘pass’).

As the Yi Jing – Classic of Changes – describes infinite change, no game is ever the same: the board is empty at the start, and the interplay of forces creates a unique pattern, a pattern that remains visible at the end of the game.

Without qi, a stone or group of stones is dead – it must have ‘breathing space.’ As lines of stones take shape into groups, they map the ebb and flow of qi across the board; those groups with much qi are lively and free, those which are constricted and ‘heavy’ often die.

During the course of play, a player’s fortunes change frequently, as in life; how the player reacts to these changes can tell them (and everyone else watching) what degree of cultivation they have reached.

Do they lose with grace? Do they win kindly?

Do they play impulsively, or calculate each move?

One can become obsessed with a small portion of the board, completely missing the momentous changes happening elsewhere. Or one can learn to view the total situation, objectively, even wisely – but this wisdom is usually learned over a long painful apprenticeship, with many lost games.

‘One improves in the game by learning to see,’ I was told.

‘See what?’ I asked.

‘What is in front of your face all the time!’ my teacher laughed. ‘You will learn to see the patterns that will determine what is to come, and when you learn to see those patterns on this board, you may learn how to see those patterns in life, as well.’

Endnotes:

[1] There is even a book entitled: The Protracted Game: A Wei-Ch’i Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy.

[2] China was thought to be like a go-board, square and divided into a 9×9 grid, and floating on and surrounded by water. Even today, weiqi beginners learn on a board of 9×9 lines.

The word “Classic”¹ is another forced label. It begins with the perception of a sage, seeing the people of the world chasing their emotions, pursuing fantasy, indulging in desires, and occluding the Real. These sages are concerned about how the deluded mind² disturbs the realm of awareness (靈地 líng dì) and about the flourishing of ignorance, so that that the untainted gift of Heaven is lost and the original basis unable to be restored in case of sudden death or maiming.

Thus they employ the power of expedient means to open the gate of guidance, to meet and lead the deluded masses back to the true path.

And thus too all those books that teach are labelled “Classic.”

“Classic” (經 Jīng) means pathway (徑 jīng), the great pathway that all must pass along. Even though reading a classic, one should not become fixed on the language. But you also cannot leave the classic and look elsewhere: you must pay attention on your own part, take those five thousand words and chew them finely, considering each stroke of each character … then suddenly you have bitten through a sentence, or even half a sentence, and that part of the classic is yours, and you can open your mouth without the words issuing simply from the surface of your tongue.

Here is where you open your own treasury, drag forth your own classic, interpreting it in inspired fashion. And this goes not only for this one classic, it goes for all thirty-six respected classics, one huge storehouse of teachings! Go through it all once from start to finish: all it will take is one big shout before it is all perfectly clear.

Right?

A sudden gust of wind over even ground,

A thunderbolt exploding out of a clear sky.

Listen! Listen!

Ode

The marvellous function of this classic is hard to evaluate

Not changing over ten thousand ages

Every line having its use, every place a safe crossing.

If you have not picked up your own clear discernment

You are not a true child of my house.

Who dares travel within?

Endnotes

1. 經 Jīng, as is frequently noted, originally meant the warp threads on a loom, and like those threads, classics are the stabilising influences that run through a culture and maintain its central principles as the warp thread of each generation pass one by one, constructing the overall design which will be that culture’s legacy. Jing is also the word for Sutra in Buddhist writings.

2. “Deluded mind” is literally (業識) yè shí, a Buddhist technical term, the “activating mind.” See Awakening of Faith. 《起言論》:“一者名為業識,謂無明力不覺心動故.”

By Li Dao-Chun

Li Dao-Chun (李道純) was a 13th century Daoist Master in the line of the famous 4th generation Master of the southern Nei Dan lineage, Bai Yuchan. Li is author of the Zhōng Hé Jí (中和集) translated as The Book of Balance and Harmony by Thomas Cleary.

What follows, which to my knowledge has not been previously translated, is the valuable preface and introduction to Li Dao-Chun’s Dào Dé Huì Yuán, his commentary on Lao Zi’s Dào Dé Jīng.

With humility, I venture to say that Fuxi’s hexagrams of the Yi reveal the primal heaven, while Laozi’s writings all depict Dào and Dé; these are the ancestors of all the classics.

Students today are unable to make out the principles in these two books – why? Mainly because it has not been passed down to them. When I had not yet mastered the hexagrams, I travelled widely to try and meet people who had achieved, those who could ignite the opening of my heart and mind to the subtle changes,¹ and which would allow me to make out the marvels of the Yi Jing.

Thereafter I exhausted everything obtained from these adepts in composing my Sān Tiān Yì Súi (三天易髓 Mutable Marrow of the Three Heavens) for the instruction of my students. Yet Lao Zi’s Dào Dé Jīng remained incompletely investigated.

One day I was instructing my student Ji An, and he brought along a copy of Bai Yu-Chan’s Dao De Bao Zhang (Precious Stanzas of the Way and its Power) to show me. I saw that the annotations closely matched the meaning of the text, except for just a few rare places. I was about to make some comments at random, then on reflection did not dare! Later two or three other students brought out annotations made by a number of experts and asked me about them.

The first thing I did was compare the different versions of the classic itself, and found there were many discrepancies: an extra word here, a missed character there –sometimes even whole sentences would be mistaken, or two characters transposed; the versions were all at variance. Sighing, I said “If the classic itself is like this, how can one annotate it?” The students asked me the reason for the differences, and I said “In the beginning it might have been a copyist mistake, or on printing they did not properly check the blocks. There, too, may have been places our predecessors were unable to understand and so they randomly added or changed the text, mistake leading to mistake and ramifying like this.”

They said “Who is right?”

I said: “He Shang-Gong’s Lao Zi Zhang Ju (老子章句 Lao Zi Chapter and Verse) and Bai Yu-Chan’s Dao De Bao Zhang (道德寶章 Treasured Chapters on Dao and De).”

They asked: “Why is that?”

I said: “Because the thread of meaning running through their writing is accurate.”

They said “What about the various annotators?”

I said: “Their perceptions are different. Each only grasps a part.”

They said: “Can you be more specific?”

I said: “Generally they make their assessments from an idea of self, rather than letting it flow out from their own chests, and thus they cannot extend or broaden the meaning. If they approach it from a ‘how to govern’ angle they are stuck with it as a text about governing; if they approach it from an alchemical viewpoint they are stuck with alchemy; if they think it is about military arts they are stuck with a book about the art of war; if they think it explains Zen subtleties, they are stuck with Zen subtleties. Some discuss principles but ignore practicalities, others talk about practice but leave out principles. As for power, tactics and strategies, sidetracks and fruitless paths leading into deviance, all of these have lost the basic meaning intended by the sage. They should know that when a sage creates a classic, the original intention is established prior to heaven and earth, comes to manifestation in yin and yang, and only then arrives in this world. It contains both practice and principles without missing either; how can one grasp one side while discussing it? That’s why I dare to speak indiscreetly and, one by one, bring out for everyone those places where the explanations contradict the meaning of the classics as set out by the sages.”

All those present said “Excellent!”

From then on the people seeking assistance increased, and they would not allow me to keep silent; therefore I made annotations, sentence by sentence, to the rectified classic, explaining its meaning, demonstrating the importance of cultivating the spirit and nourishing qi. I also summed up the line of thought at the end of each chapter in order to clarify the fundamental and original sequence. Lastly I composed a verse for each chapter which showed the way to clarify the heart-mind and perceive essence. As for religious, political, moral and daily use by the average person, including instructions on how to practice the Way, generally and specifically, obvious and subtle: nothing has been omitted from it.

At the front of the book I placed a section clarifying terminology and a section investigating the rationale in order to eliminate doubts about similarities and differences in the classic.

I called it Accord with the Origin of the Dao and Its Power to help later students discover a rich understanding, entering in through the explanations and hopefully not falling into bias, enabling them to reach the Dao and return to the Origin. The problem with it is that the style is vulgar and is nothing but a straight explanation of the meaning of the classic, and even that I do not dare say is correct. Nonetheless this can draw the attention of my friends to a few areas of comparison between the various texts.

Preface composed at dawn in early summer of the year 1290

by the student from Duliang (Hunan), Qing An (Clear Hermitage),

Yingchanzi (Master of the Shining Toad): Li Dao-Chun, also known as Yuan Su.

Endnote

1. Li Dao-Chun defines xīn yì “Changes of mind consists of methods of transformation”: “心易者,易之道也… 观心易贵在行道” See Cleary Book of Balance and Harmony, p.16.

Question:

When I investigate directions for the great medicine of the golden elixir, there are many terms such as Sun and Moon, Dragon and Tiger, Lead and Mercury, Kan and Li, Firing Method, Cosmic Orbit, and also trigram and hexagram symbols, and even further terms like “the supine moon” and “the cauldron of cinnabar sand.” Not only are there multiple terms, there are all sorts of activities. Is it just that there are many names for one thing? Or do each of the many terms specify something different? If we look inside, it is formless; seeking outside there are images, and so is the trick in doing? or is the trick in stillness? The ancients said that that which involves doing is not the Dao, but they also said that if one is addicted to stillness this is only sitting in oblivion like a withered tree.

I am confused and don’t know how one should enter the path which leads to the innermost recesses, and thus respectfully request an explanation.

Answer:

The first sages looked up to observe celestial phenomena, they looked down to observe the principles of the earth. They observed that which is close by looking within their own bodies, while the distant they discovered in external things. Their creation of alchemical sayings had the intention of establishing long life without death, to clarify people’s minds; actually it is a unified principle.

The beginning entrance is in yin-yang and the five elements, the final arrival returns to unlimited formlessness (hùndùn wújí 混沌無機).

The alchemical methods you mentioned each has their basis, yet each sets up an explanation and holds to a particular view, and thus it is hard to bring all of them into unanimity. The important thing is who I meet, what is transmitted to me, the fruits of that transmission and what I do with it all.

[The symbols vary widely: for example, if we use terms centered] in heaven it is sun, moon, stars and constellations; in earth it is birds, beasts, grass and trees; in people it is husband, wife, son and daughter. If we use the Yi Jing (Book of Changes) names of trigrams to discuss the matter, then it will be Qian, Kun, Kan and Li; if we use wu xing (five phases) to discuss the matter, it is metal, wood, water and fire; if we talk in terms of medicinal substances, it will be silver, lead, cinnabar and mercury. If we use the terms of the search for immortality (dān dào) then it will be dragon, tiger, crow and rabbit.

In its utilisation there are the names platform, oven, cauldron and stove; in its practice there are the images of rising, falling and mating together; in its embodiment there are the changes felt as floating, sinking, clear and turbid; as you follow it there are the signs experienced as yin, yang, winter and summer.

The sages thus said: gather using medicinal substances, refine using the firing process, congeal it to form the Cinnabar Pill, and you transcend the ordinary and become a human sage.

Therefore [regarding your question about looking inside or outside] when you obtain it internally, you do not become mired in internal images, when you obtain it externally, you do not look for it only in external objects. This is the meaning of “neither object, nor image”.

道家为什么强调修性,强调气功修炼?道理就在这里。修性,是吧基础立正,一切功法源于大道,服务予大道。心不正,性不纯的人不得入其门。这最低的要求是不得杀生,不以功法谋私利,做坏事。而内功的修炼可以引出千百种功法来,这些功法都是一个个阶梯,由此 到最高境界去。停留在一种功法上, 也是一种执著,那是不悟大道。

Why do Daoists emphasize cultivation of essence and development of inner power? Cultivation of essence is setting up the basis correctly; then all exercises and methods are rooted in the Great Way and work for the Great Way. People whose minds are not straight and whose essence is impure cannot enter the gate. The minimum requirements are not taking life and not using Daoist methods for personal gain or for doing bad things. The cultivation of inner power can bring forth countless methods of practice; these methods are stepladders by which to climb to the highest states. To stick with just one method is a kind of attachment, a failure to understand the Great Way.

(from Opening the Dragon Gate,

Thomas Cleary’s translation of

Da Dao Xing 大道行

by Chen Kaiguo and

Zheng Shunchao, chapter 15)

The Chan teacher Yaoshan was well known in the province of Jiangxi, although he rarely left his monastery. The governor of the province, a neo-Confucian called Li Ao, had heard that perhaps the Chan people knew something. He decided to visit.

So he changed out of his official garments and made his way to the monastery on foot. Despite his precautions, all along the route the mayor of each city and village headmen would come out personally to greet him with an entourage to welcome the arrival of this important official.

Finally Li Ao made his way up the mountain and was shown into Yaoshan’s room.

The master was facing away from him, reading a classic text by the light of the window. Li Ao could see the Yaoshan was tall and thin, almost emaciated from his vegetarian diet. Li Ao stood silently behind him, but the master did not turn. Finally the young monk attendant cleared his throat and said ‘Master, the provincial governor is here.’

‘Unh,’ Yaoshan said, appearing both to hear, and not hear, what had been said.

Li Ao’s ire rose, and turning away, he said ‘Hearing the reputation is not as good as seeing for oneself.’

Yaoshan let him walk a few steps, and then said ‘Governor, why do you slight the eye in favor of the ear?’

Li Ao got a shock, and turning back begged forgiveness. Then he asked ‘Can you tell me about the Dao?’

Yaoshan looked at him, then pointed once upward and once downward.

He paused, then asked ‘Do you get it?’

Li Ao, realising the master was the real thing, shook his head.

Yaoshan pointed upward again and said ‘Clouds in a clear sky.’

He pointed downward and said ‘Water in glass.’

Li Ao later wrote a famous poem enshrining the incident:

练得身形似鹤形,千株松下两函经;

我来问道无余说,云在青天水在瓶。

Practice made him resemble a crane;

Two classics held in a forest of pines.

I asked the Dao, and he wasted no words:

‘Clouds in a clear sky, water in glass.’

Zhang Bo-Duan carefully composed the book Wu Zhen Pian (Understanding Reality) after trying three times to pass on his knowledge, and three times failing due to having chosen unsuitable people. In the postscript Zhang Boduan said

“In this book of mine, everything is made ready for you, the verses and songs have the firing process of the great elixir, and all the subtle directions. Those who have an affinity for this matter must have the bones of a transcendent, then when they read this book carefully and with wisdom it will inspire clarity. They can search the text to unravel the significant meaning of terms, there will be no need for personal oral transmission by my humble self. This book is in fact a bequest from Heaven, not my own presumption.”

A cicada’s chill keen broke the first pause in the hard rain.

This night, there is only your face.

Dismal drinks in the traveller’s tent by the city gate,

Boatmen anxious to push off in the lull

– still we hold back.Shameless, we grip hands, tearful

And choked with silence.The thought of going, going:

Haze like smoke over the water a thousand miles;

Dull cloud misting deep

The broad skies of the South.Always and everywhere, severed love rends the heart

But at so bleak an autumn, utter torment.Drunk tonight, where shall I wake?

Poplar and willow on the banks,

The rise of the dawn breeze

As the moon sets.There will be so many years, and so many lovely scenes

— all empty;

And though there be

A thousand rousings of my heart

— with whom shall I share them?Liu Yong 987-1053

This is a poem in the cí form (‘ci’ is pronounced like ‘tsih’) which borrowed popular tunes from Central Asia as a format for rhythm and structure upon which a new poem was constructed. The tempo and length could be either fast and short, or slow and long; this poem is an example of the latter, called màn cí.

Here is the poem in running script by the famous contemporary calligrapher Wang Dongling.

Liu Yong was a master, and some say the originator, of the long and slow form of ci poetry. (This was also the favourite form of Li Qing-Zhao, the great poetess). Liu travelled to the capitol Kai Feng to take the imperial examination. He failed each year, and remained to try again the next, until he was forty-seven. In between exams he spent much of his time in the urban pleasure centres, and many of his poems describe the lives of singers and courtesans, and the life of the emotions.

Simple in language, yet carefully crafted and hauntingly delicate, they remained widely popular for centuries, so that in the words of a later critic “the poems of Liu Yong are sung wherever a well has been dug.”