A cicada’s chill keen broke the first pause in the hard rain.

This night, there is only your face.

Dismal drinks in the traveller’s tent by the city gate,

Boatmen anxious to push off in the lull

– still we hold back.Shameless, we grip hands, tearful

And choked with silence.The thought of going, going:

Haze like smoke over the water a thousand miles;

Dull cloud misting deep

The broad skies of the South.Always and everywhere, severed love rends the heart

But at so bleak an autumn, utter torment.Drunk tonight, where shall I wake?

Poplar and willow on the banks,

The rise of the dawn breeze

As the moon sets.There will be so many years, and so many lovely scenes

— all empty;

And though there be

A thousand rousings of my heart

— with whom shall I share them?Liu Yong 987-1053

This is a poem in the cí form (‘ci’ is pronounced like ‘tsih’) which borrowed popular tunes from Central Asia as a format for rhythm and structure upon which a new poem was constructed. The tempo and length could be either fast and short, or slow and long; this poem is an example of the latter, called màn cí.

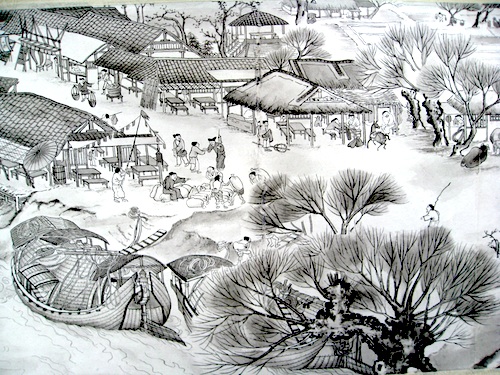

Here is the poem in running script by the famous contemporary calligrapher Wang Dongling.

Liu Yong was a master, and some say the originator, of the long and slow form of ci poetry. (This was also the favourite form of Li Qing-Zhao, the great poetess). Liu travelled to the capitol Kai Feng to take the imperial examination. He failed each year, and remained to try again the next, until he was forty-seven. In between exams he spent much of his time in the urban pleasure centres, and many of his poems describe the lives of singers and courtesans, and the life of the emotions.

Simple in language, yet carefully crafted and hauntingly delicate, they remained widely popular for centuries, so that in the words of a later critic “the poems of Liu Yong are sung wherever a well has been dug.”