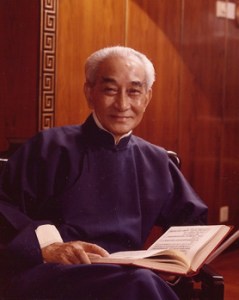

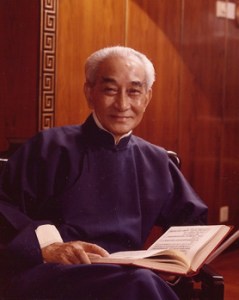

Nan Huaijin (Nan Huai-Chin), who passed away not long ago, was a recognised vajra master in Buddhism, but was unusual in that he was also thoroughly schooled in Confucianism and Daoism.

This poem from Zhang Bo-Duan (author of the Wu Zhen Pian: Understanding Reality, one of the most famous classics of Daoist alchemy) was explained by Master Nan during a seven day Zen retreat held in China.

Mater Nan led into the discussion by comparing modern physical science and Buddhist sciences:

“Studying Buddhism is a science of life. It is different to natural science in that it does not use the physical things of the external world, but instead uses the functions of one’s own body, the five sense organs, and the biggest organ, that of the brain. But it is using the brain to turn around and investigate itself, the mind to turn around and look for one’s own mind within.

There is a Daoist, one of the patriarchs of the Southern school, Zhang Zi-Yang (Zhang Boduan). A Daoist, yet he was also thoroughly versed in Buddhism, especially Chan in which he was a high illuminate. This True Man, Zhang Ziyang, wrote a truly excellent poem about the experience of quiet sitting in Chan.

心内观心觅本心

xīn neì guān xīn mì běn xīn

Observe the mind within the mind to search for the root mind.

This is what we were just speaking about: turning around to look for one’s own mind; interior observation of one’s heart, the effects of our thoughts and feelings. This is mind, the function of heart/mind.

When I say “heart” I do not mean the physical heart, it refers to what we now call the brain, the feelings, knowledge, sensations … all these caught up together is what we are calling heart/mind, this basic function.

Before we were born of our father and mother, before we had become a foetus, did this mind exist? This is what we are looking for, not what Western philosophy talks about as mind. What Western philosophy means by ‘mind’ is what is known in Buddhism as the function of the sixth consciousness: the thinking mind, the thoughts in the mind, that is the sixth consciousness.

It is not mind as a whole.

We are talking about mind as a whole.

心内观心觅本心

xīn neì guān xīn mì běn xīn

Observe the mind within the mind to search for the root mind.

Where is that original mind? What is the origin of the origin? Without my brain, without my body, where after all is that heart/mind?

Here is the second sentence:

心心俱绝见真心

xīn xīn jù jué jiàn zhēn xīn

Cutting off thought after thought, you will see the true mind

All the thoughts and feelings inside you, all that is happening, all come to rest, all quiet and still. Slowly, slowly, they all cease; totally and absolutely still and quiet, all errant thoughts stopping. Feelings, knowledge, everything, all rests.

“Perceiving the true heart/mind” (见真心jiàn zhēn xīn) – you can then observe your own true and proper fundamental origin (真正根源 zhēn zhèng gēn yuán), the function of the root mind.

The third sentence:

真心明徹通三界

Zhēn xīn míng chè tōng sān jiè

The true mind penetrates with clarity throughout the three realms

If you can find the foundation of the root mind, the root essence (本性běn xìng), if you understand it, realise it, and truly verify it—not theoretically, mind you, but throwing your whole body and mind into this search to verify it—then one can transcend this material world, leap beyond the “three realms” (of desire, of form, and of formlessness). Hence “The true mind penetrates with clarity throughout the three realms. ” Then, he concludes:

外道邪魔不敢侵

waì daò xié mó bù gǎn qīn

Heretics and evil spirits dare not encroach.

Ghosts, devils, spirits, none of them dare to molest you. Zhang Zi-Yang was very well-known, an accomplished expert in both Buddhism and Daoism, in what they call the Southern School of Daoism. He was one of the patriarchs of this Southern School.

Observe the mind within the mind to search for the root mind.

Cutting off thought after thought, you will see the true mind.

The true mind penetrates with clarity throughout the three realms.

Heretic and evil spirits dare not encroach.